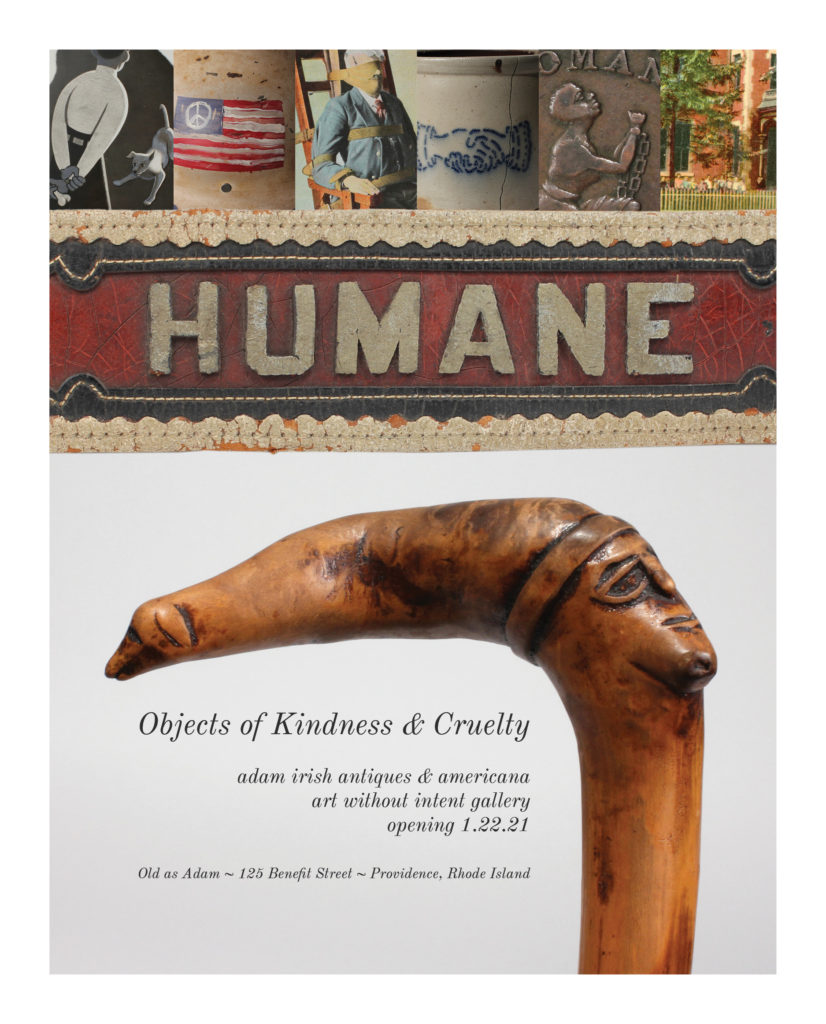

Over a year ago, I came across a nineteenth-century fireman’s leather belt emblazoned with the word “Humane.” Struck by the purity of its message, I began to look for other humane things, and so grew this collection of contradictions.

Humane objects reflect our compassion for the powerless and oppressed. Some recall individual acts of kindness and generosity. Others mark transformative changes wrought by radical political and social activism.

These things embody our best intentions, but also our worst hypocrisies. More often than not, the term “humane” is deployed to disguise the inhumane. The collection reveals chips in the thin veneer of palliative concern applied over injustice and suffering.

Still other objects I’ve collected here stand outside of topical relevance and history but give shape in metaphor and spirit to a concept so kind and so cruel.

More than an inquiry into the past, “Humane” is intended to be an archaeology of the present. Some things in the collection may elicit moral indignation or incredulous laughter, and many should. But in their time, they embodied values seen as natural or were in fact celebrated on the highest planes of enlightened ethics. But before we scoff and disavow the troubling dimensions of these items as belonging to another time, we should consider that future generations will look upon our own decontextualized material culture with the same moral revulsion. In the past as in the present, humane norms are often arbitrary and unquestioned, still determined by political sleights of hand and the willful myopia clouding our collective conscience.

A sincere call to act with our hearts, a utopian demand to right the wrongs, a benevolent gesture to cement power, an attractive curtain to obscure evil: in each, the humane opposes or inverts reality. The objects here give form to these aspirations, delusions, and distractions in the hope that they may help us better discern the humane from the inhumane in our own time.

Adam Irish

January 2021