Bicycle Forerunner

Two-wheeled pedestrian velocipede / wood, wrought iron / American / c. 1820s

Rare and important American “dandy horse” pedestrian-driven velocipede, New England, c. early 1820s. The forerunner to the bicycle, this curious kick-propulsion two-wheeler is a uniquely American interpretation of the velocipede, an invention which for a brief time garnered fascination and scorn across the United States. Historians estimate no more than one hundred American velocipedes ever rolled the nation’s streets, and in this singular example we find an American vernacular version of the short-lived “mechanical horse.”

Description

Found in Vermont, this extraordinary proto-bicycle stands apart for its striking form which is at once primitive and refined. Given the ungainly elegance of velocipedes in Europe and later in American cities, in all likelihood this stark, unadorned design was conceived by a country carriage maker or wheelwright who saw an image of the curious vehicle in a newspaper. His creation has a wood-pegged mortice and tenon frame in old blue and yellow paint, wood-spoked wheels with iron rims, and a wrought-iron front fork driven by brass-riveted turned wooden handles. The seat is upholstered, and though stuffed with ample horsehair, a rider would have felt more than minor discomfort rolling down a cobblestoned street. With its angular frame, clean lines, and functional design, the aesthetic of this country velocipede is not only fresh to the modern eye, but even futuristic, anticipating bold Constructivist forms by a century.

The Meteoric Run of the Velocipede

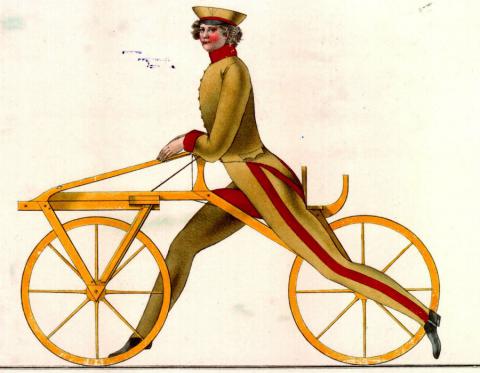

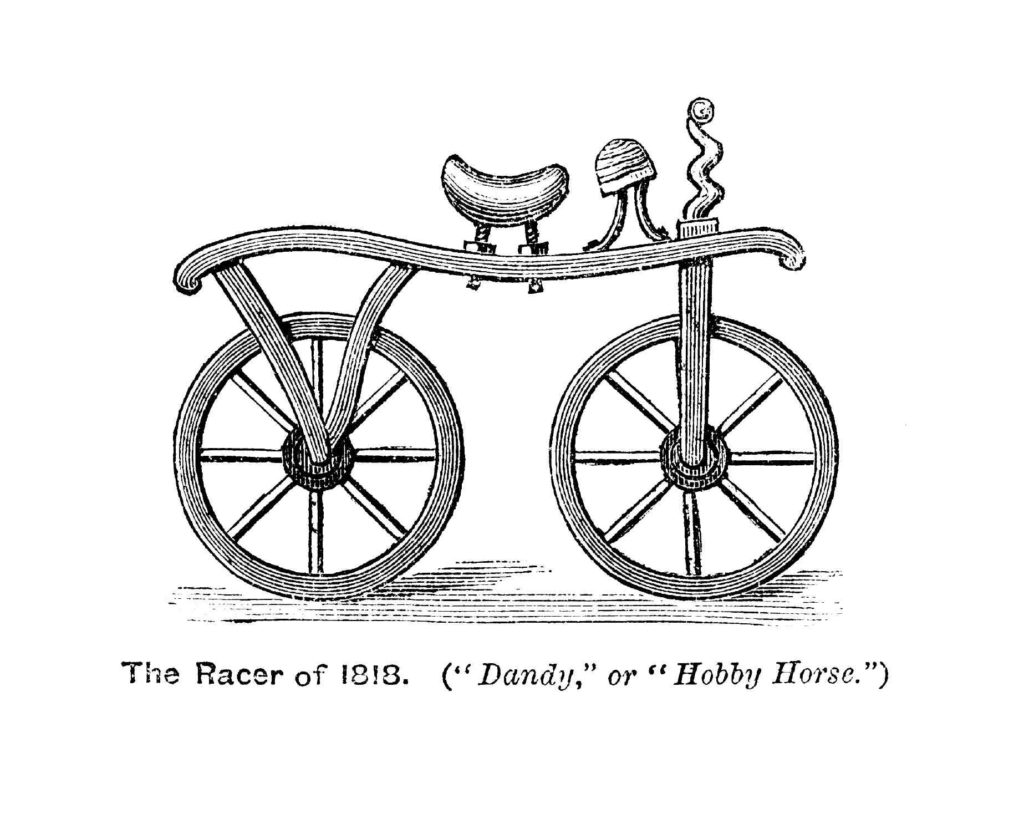

Cutting-edge technology in its day, this improbable two-wheeled device was designed by Karl von Drais, an eccentric German inventor obsessed with the idea of a horseless carriage. Drais unveiled his “laufmaschine” — translating to “running machine” — in 1817 in Austria. The invention was better known by the names “draisine” and “velocipede” (from the Latin words meaning “fast foot”). Pushing off one foot and then the other astride the velocipede, Drais contended that the use of his invention could speed the natural acts of walking and running, doubling the speed of a walker and matching the speed of a galloping horse when running. To promote his invention, Drais introduced a pamphlet with designs including a tandem and three-wheeler accomodating a lady passenger, as well as optional sails and umbrellas. Though the draisine captured imaginations across Europe, its practical limitations were all too apparent given the terrible state of rutted and muddy roads. Although it briefly caught on for its sporting capabilities as an “accelerator” and races were held in Paris, by 1818 the draisine had been dismissed as a toy on the Continent.

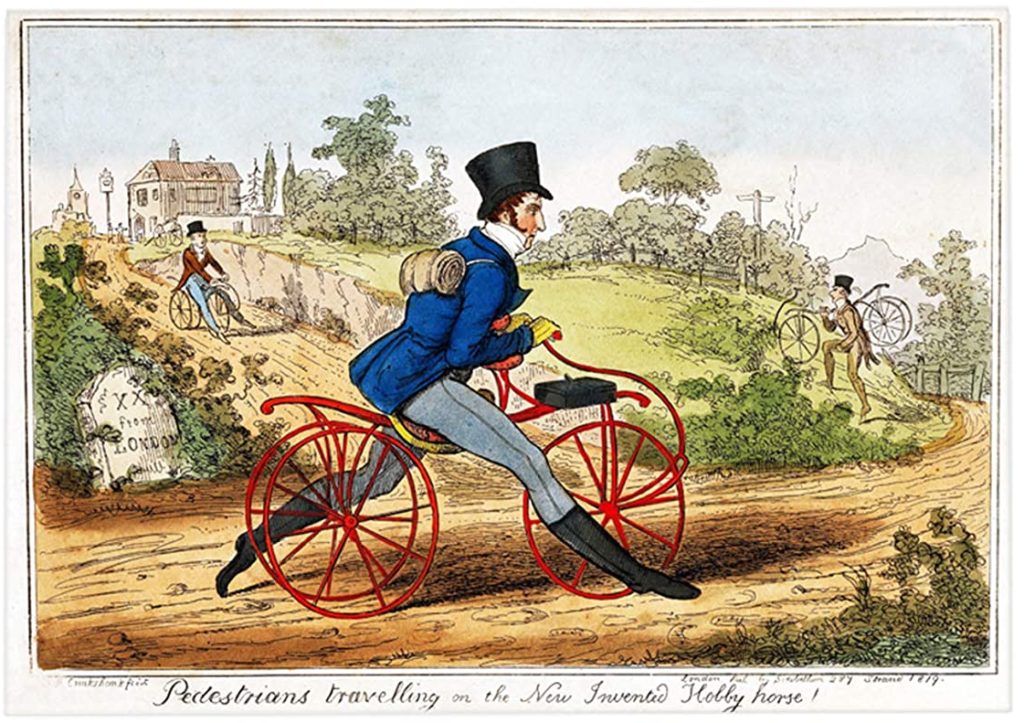

In England, however, the concept found a receptive audience with the 1818 introduction of Denis Johnson’s “hobby-horse,” which outmatched the draisine for elegance and performance. It was soon taken up by attention-seeking young men, who commentators derided for their “dandy-horses.” The foppish riders soon faced fines and arrest for endangering pedestrians on city sidewalks. But the interest in the hobbyhorse spread, seeing the development of organized races, a model designed for women, and even a riding school. Though long-distance rides at impressive speeds were recorded, the British velocipede quickly faded like its Continental forerunner. Given a rash of injuries, the London College of Surgeons condemned the machine in 1819, relegating it to obscurity.

As London dandies strode on their hobbyhorses, Americans also began experimenting with the velocipede. J. Stewart, a Baltimore instrument maker, was the first to introduce an American version, the “Tracena,” in late 1818. Though admitting such a “land carriage” had promise, one critic wrote Stewart was “too sanguine. It appears to be suited only for good level roads” but that it held hope “as an instrument of graceful and manly exercise.” Though he supposedly received a number of orders from young men, his Tracena did not catch on.

However, an inspection of the vehicle piqued the interest of Philadelphia portrait painter Charles Wilson Peale, who commissioned his own velocipede and displayed it in his private museum, garnering significant profit from the admission of curious visitors. Soon, several others were found on Philadelphia streets, which one journalist described as “exhibited everyday for the amusements of the spectators at the public squares and gardens — any person rides them that pleases.” One entrepreneur offered velocipedes for hire at Vauxhall Gardens and enthusiasm for the invention was such that J. Stewart relocated to Philadelphia to promote his own line.

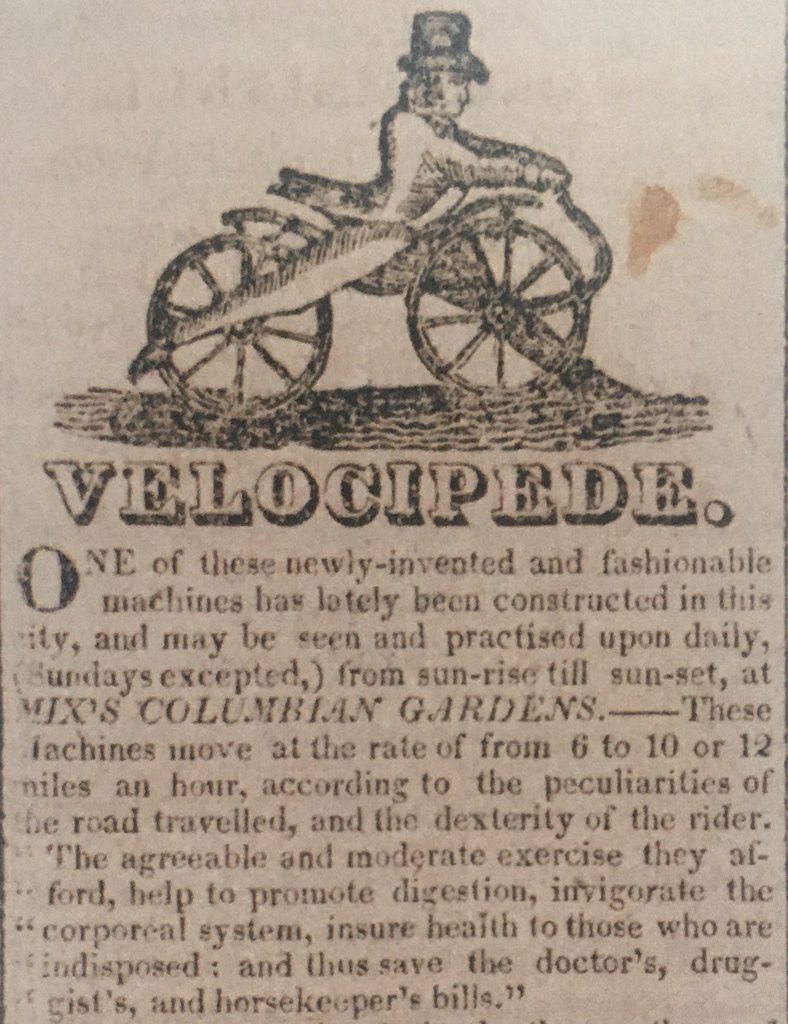

Meanwhile, in New York City, an enterprising English entrepreneur touted the hobbyhorse to skeptical New Yorkers, going so far as to open a gas-lit indoor velocipede rink near Bowling Green in lower Manhattan. In well-circulated advertisements, the proprietor offered a fleet of velocipedes for hire, on which a patron could ride “between six and twelve miles an hour, free from any molestation or danger.” The rink also touted the health benefits, arguing a riding habit would “promote digestion, invigorate the corporate system, and ensure health to those that are indisposed.” However, authorities in both Philadelphia and New York did not look kindly upon the dandy-horse speeding along public thoroughfares: Philadelphia liberally fined riders while New York declared them a “public nuisance” and banned velocipedes from the streets altogether. By 1820, the mechanical horse in both cities rolled into obscurity.

New England enjoyed a brief diversion astride the hobbyhorse as well. Wheelwright and chaise maker Ambrose Salisbury of Boston debuted his own velocipede on city streets in 1819, attracting curious crowds and packs of boys, captivated by its “rapidity of its motion” and “singularity of its shape.” Salisbury soon invited the public to inspect his product in his showroom, though interest would be short-lived. A sardonic observer said the vehicle might briefly replace that “old-fashioned animal called a horse” since “Boston folk are always fond of novelty” but that a horse would, in the end, prove “more serviceable in climbing a hill, or passing a snowdrift.” The velocipede proved no match for Beacon Hill and Boston’s snowy streets, and likewise vanished.

In New Haven, however, the mechanical horse found its most receptive audience. A promoter named John Mix hired local carriage makers to fashion several models in 1819 and rented them out for rides in Columbian Gardens. Yale students became an enthusiastic clientele and soon New Haven was the only American city where “great numbers” of velocipedes plied the streets. A local newspaper admitted the devices “possess some advantages for exercise, and may answer a useful purpose,” but excoriated “sundry and wild riders” on their “wooden horses” who terrorized sidewalks after dark. Another New Haven newspaper took a harsher view, arguing that “these machines, with certain animals attached to them” should be banished from city sidewalks, going so far as to urge citizens to “seize, break, destroy, or convert to their own use as a good prize, all such machines found running on the sidewalks — taking care not to beat or in a wise injure the poor innocent jack-asses.” With public opinion against the velocipede, it vanished here too by 1820.*

Though we will never know how rural Vermont townsfolk reacted to the presentation of this vernacular version of the velocipede, given the vehicle’s reception elsewhere, it seems likely that the improbable wooden horse was greeted with mockery and derision. In one provincially-minded dismissal of the velocipede, which one could imagine spoken in a remote rural New England town, an American critic wrote “transatlantic nonsense…is capable of exciting curiosity, no matter how ridiculous.” In any case, given the state of roads in early nineteenth-century American towns, the velocipede’s maker may have been unable to ride his creation at all and set it aside as a stillborn dream.

Today, theorists speculate that had the velocipede met a warmer reception, the addition of pedals and the invention of the bicycle as we know it today might have occurred by the mid-1820s. Instead, cast aside, the two-wheeler would take half a century to reemerge.

Designed by a country wheelwright surrounded by mud-rut roads, this impractical two-wheeled vehicle was propelled forward not by foot, but by the American drive to innovate and the creative vision of its maker.

Condition

Handsome timeworn condition with an untouched surface. The wheels are fragile and the front is missing a spoke and piece of the felloes (the wooden outer rim). Otherwise, the piece is complete and all-original.

Measurements

Approximately 5 feet long

Shipping

Given the size of the piece, shipping for this item is an additional charge. Complimentary delivery available in parts of New England. Free pick-up in Providence, R.I. Please contact me for a shipping estimate by clicking here.

* For more on the velocipede, see David Herlihy’s wonderful book, The Bicycle: A History, from which I derived much of my source material:

Herlihy, David V. Bicycle: The History. United Kingdom, Yale University Press, 2004.