Provenance Prize Winners, Fall 2014

Sponsored by Old as Adam and Book & Bar

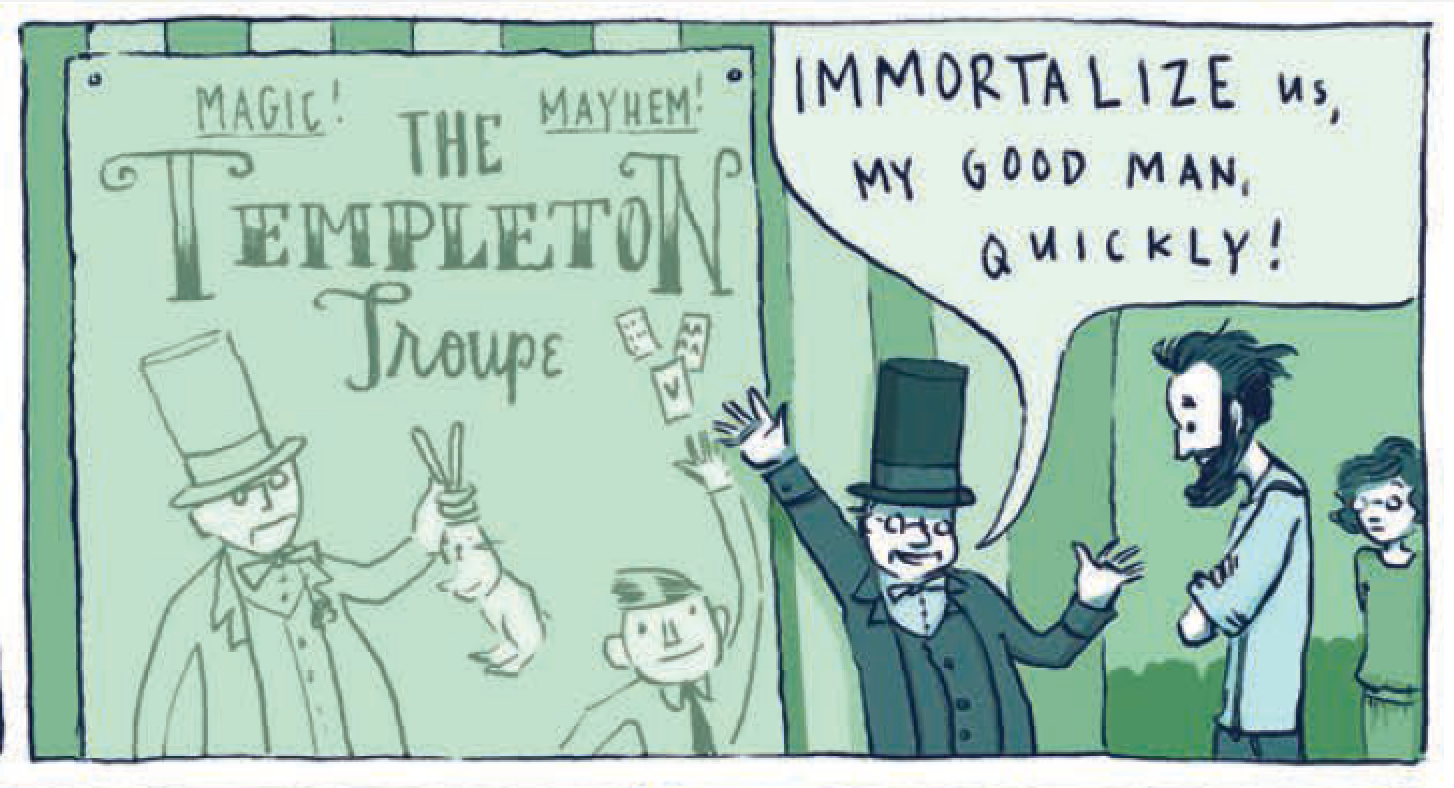

THE SUBJECT: Folk art hand-carved wooden magic show, probably first quarter 20th century. The left figure is a ventriloquist with dummy, the center a magician pulling a rabbit out a top hat, the right figure an older-looking woman bent over in a chair. Carved from pine.

FIRST PLACE

The Coppice

An illustrated short story by Abbie Halpin. Click here to read her wonderful winning submission.

SECOND PLACE

The Magic Show

By Christopher Volpe

In the first dream he was standing at the magician’s table, which was draped in taffeta with a wildflower print. With an easy snap of his fingers over the silk hat’s brim, a fawn-colored rabbit appeared, ears twitching, to a chorus of astonished laughter and applause. He bowed again and again to the warm sound, wrapping it around himself like his favorite blanket.

Eustace’s grandparents had given him the toy: a group of three rather rudely sculpted figures. There was a magician pulling a rabbit from a hat, a ventriloquist with a dummy on his knee, and a third, seated figure with its face veiled and hidden, head bowed on a matronly breast.

Someone told him it was grandmother Horatia’s idea; grandpa Delbert had carved it from a limb he’d hewn off the farm’s largest oak. Birthdays were always special, of course – grandma and grandpa, nut cakes later, and best of all – no chores.

Eustace loved the toy and wanted it near him whatever he did. He first dreamed of the magic show the night his mother placed it by his bed. “Momma,” he’d said, “can we live with grandma and grandpa, in our house, forever?”

“Of course, my little magician,” she said.

In the second dream, Eustace was the ventriloquist now, speaking to his miniature counterpart, asking questions and leading the answers – or was he the dummy, answering and asking questions of the adult? He couldn’t tell, nor could he guess the time; the voices flew like birds around his head. Instead of the theater stood a dimly lit village, alleys deep with emerald and violet shadows. People he knew and didn’t arrived and departed. He heard someone, possibly himself, talking incessantly.

“So you want to live forever? How’s that going?” said the ventriloquist, or was it the dummy? “Well, it’s working so far.”

The audience exploded into strangely loud laughter. His cheeks burned as he squinted past the footlights. Someone just visible made gestures with a series of grotesque signs that Eustace was sure meant to warn him of something.

The hum of the audience confused itself with sounds from the forest – throats rustling, twigs snapping, water in leaves, and distant, high-pitched laughter – the drone of it buzzed in his head, the natural unnaturally amplified. The scene changed again and he was desperate to find someone he’d lost, very late for something important. The stage lights blurred the way.

In the third dream he was everywhere and nowhere and then he was cold. Night clouds billowed over a rank stand of locust trees, through which he dimly discerned the familiar setting. The stage was just visible, but the crowd’s noise was absent, in its place an almost palpable silence. Eustace knew something was out there – something unspeakable, not to be seen, something bad. Overhead, as they had for millennia, sailed the night clouds and the moon.

He willed himself to become the magician again but knew instantly that it wasn’t to be. Turning, he confronted a shadow that resolved itself into a figure. It was the third player, the seated one, the supposed old woman with her face behind a veil. The figure’s downcast head was elongated, tapering snout-like toward the chin, eyeless, nose-less, mouth-less, and mute.

“Take off the veil,” Eustace heard himself saying. The anonymous, faceless thing sat unmoving. “Take it off!” he shrieked. The fabric sagged vaguely over the two large eye sockets beneath.

“Take if off – show yourself!” he commanded. The hair on his neck bristled. “Why won’t you show yourself?”

The audience had gone, and nor were the house lights coming on. He stood there, uncertain. Before him sat the still, hooded figure, very slowly bobbing and nodding in the dark.

THIRD PLACE

A Ventriloquist’s Tale

By Michael Lohmeier

Journal entry (page 1), October 1923

I speak for both of us when I say I’m a ventriloquist by trade. I sometimes forget if Marcus is moving my lips, or if I’m moving his. He’s clever, that one. We’ve been touring with the magician, Huntington, since 1921.

Regina joined the show about six months ago. She does a psychic act, except most of the time it doesn’t look like an act. Marcus and I don’t know what to make of her. Huntington introduces her as, “The Seer Regina.” She knows how to work a room, I’ll say that. When she takes center stage, the Marcel waves in her copper-red hair reflect the spotlight and her skin is so white she seems to glow.

Sometimes, after a show we go to a private residence and give a séance. I act as a kind of butler, passing a tray of drinks (while overhearing useful conversations that I pass on to Huntington, natch) and providing a needed prop on occasion. My real job is to help achieve some of the ghostly effects. The rubes are all too eager to believe in spirits of the dead hovering just off-stage, waiting to be contacted. Nobody suspects the butler.

In Omaha we were invited to the mansion of a cattle baron named Carson to give an aftershow séance. After the usual visit with the spooks, Carson’s wife, Irene, asked Regina to tell her son’s fortune. Regina took young Samuel’s hand and immediately fell back in her chair in a trance. I’d never seen her do this before, but it was very effective. She spoke in a strange voice without an accent. “Don’t go, don’t go—delay your journey. Please don’t go!” she pleaded, very convincingly. Regina then went quiet and fell into a deeper trance. Huntington’s wife, Irene, leapt from her chair and ran from the room. When things had quieted down and Regina had come out of her trance, Carson told us that their oldest son, Samuel, had been accepted to Chicago University and had picked up his train ticket that day. Irene returned to the room with something in her hand that she dramatically burned in the fireplace—the ticket, of course.

Back in Huntington’s hotel room we compared notes.

Huntington congratulated Regina on her impressive impromptu performance. “How did you know about the boy Samuel’s impending train ride?” I’d wanted to know the answer to that question myself.

Regina looked Huntington in the eye and asked, “What train ride?”

Huntington gave a short laugh and said, “The one you told Samuel not to take.”

“The last thing I remember was concluding the Talking Bell routine,” she said.

“Wait—you really fainted?” I asked.

“Yes. This is all quite strange. I’m very tired. Good-night, gentlemen.” She glided out of the room and Huntington and I looked at each other. Finally, Huntington said,

“Extraordinary.” We never did the fortune telling bit again after that night.

A week later, the headline of the Denver Post read, “34 Killed Dozens Injured In Horrific Train Wreck.” The train was on its way to Chicago from Omaha.

A month later our mail caught up with us in San Francisco. There was a package postmarked Omaha. Inside was a wooden carving of Marcus and I, Huntington pulling a rabbit from a hat and Regina in that strange trance position she was in that night at the Carsons. There was a note from Samuel enclosed that said, “Thanks for saving me. My dad thought you were fakes until the fortune part. With Gratitude, Samuel.

PS—I hope you like my carving.”

Marcus said it was worth a fortune.